When you run out of cash in three weeks, everyone notices.

But running out of cash in 13 months… when your equipment fails, a debt balloon hits, or your expansion launches late… can be just as dangerous. It just hides better.

That’s the silent threat of poor capital planning. It doesn’t show up in your inbox this week. It builds slowly and shows up exactly when your team expects you to lead.

Most businesses spend their energy on short-term cash. That’s important. But it’s not enough.

Today, we’ll fix that by helping you:

- Understand the spectrum of capital needs

- Build a clear, 18-month capital planning model

Let’s get to work.

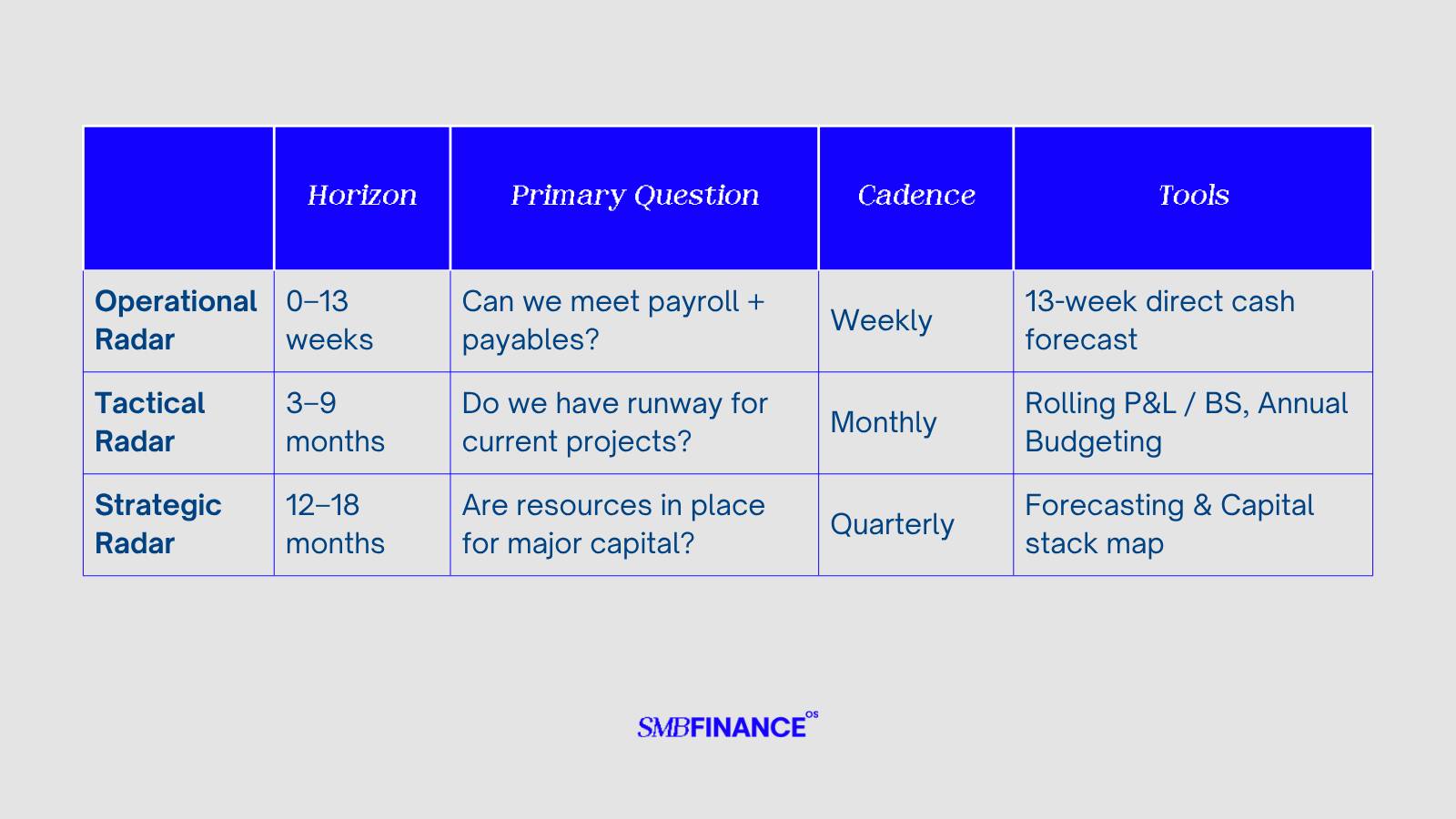

THE CAPITAL RADAR SPECTRUM

Think of capital forecasting like a radar system. Some radars have a short range while others are long range. And each of these has different purposes. In the same way, your capital/cash radars answer different questions:

Too often, you’ll see businesses only monitor one or two of these areas. It’s important that all of these are monitored.

Each type of capital decision requires a different lens and cadence. Understanding what each decision is is key to applying the right tools.

- If the question is shorter than one payroll cycle → operational.

- If it changes headcount or debt → strategic.

- If your lead time to raise funds is longer than your runway → you’re already late.

During the CashOS series, we talked about the short-term Operational Radar in the 13-week cash flow. Through our series last fall, PlanningOS, we talked about the Tactical Radar & Strategic Radar.

Today we’ll be adding to that Strategic Radar with capital planning.

BUILDING A STRATEGIC CAPITAL FORECAST MODEL

To really dig into our Strategic Radar/18 month plus plans, we need a system to reveal these potential costs and needs. The key tool for this is an Indirect Cash Flow Forecast.

And lets start here: We don’t need perfection, just visibility. You want to see the mountain before you slam into it so you have time to make plans.

Start with a lightweight model and forecast revenue, expense, CapEx, and cash movement by month.

REVENUE SCENARIOS

Forecasting revenue is “easy,” right?

We always have a tendency to be over-optimistic, which means we can easily overspend with a bad revenue scenario. So, when forecasting revenue, how do we make it more accurate?

We take into account as many variables as reasonable. Some good things to consider:

- Historical Sales

- Current Contracts

- Sales Pipeline

- Sales & Marketing Initiatives

- Capacity Constraints

- Market Conditions

Once we’ve looked at these, we can decide how to weight them. This is a guess, but based on historical data, you can usually have a decent feel. Lean on history, contracts, and pipeline, as these are the most “real” numbers. The rest are more speculative.

Keep this as simple as possible. Complicated forecasts and models sound like a great idea. But complicated forecasts are often hard to understand. It’s better for the parties reading the forecast to be able to understand the variables, which means reducing the number of things impacting each number.

EXPENSE PLANNING

Expenses should be approached in two ways:

- Percentage of revenue

- Budget approach

Start with a percentage of revenue on COGS and all expenses. Then go through them line by line. What is changing? What is staying the same?

Take historical data and known changes and consider some key factors:

- Committed overhead (rent, insurance, software expense)

- Wages (both new hires and estimated raises)

- New initiatives (Sales & marketing, new lines of business, etc)

I like to intentionally overestimate expenses by 5-10% to ensure profitability is strong in any scenario.

Cost of Goods Sold often increases at the same rate of revenue growth, but overhead expenses are more likely to have a “step-up” effect. Be sure you look and understand the potential step-up points for your main expense categories so you don’t get surprised.

INTEGRATING THE STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS

We did all this work to understand what profit we’re generating from your Income Statement. Now we need to understand the Statement of Cash Flows.

Remember, the Statement of Cash Flows is three types of cash movement:

- Operating Cash

- Investing Cash

- Financing Cash

Profits from the Income Statement come over the Statement of Cash Flow and is your starting point for cash generation. Then adjust non-cash charges, like depreciation, to get Operating Cash Flows.

For simplicity's sake, on the rest of the statement, let’s focus on the changes related to CapEx, debt, and distributions.

MAPPING CAPEX SPEND

We’ve dug into CapEx and the difference between maintenance and growth CapEx in the past, so I’m not going to rehash it here. Go to this newsletter and read up to go deeper.

Today, I want to focus on creating a plan and “mapping” CapEx for the next 18 months.

This is the practice of taking the identified CapEx needs and plugging in the spend on the timing you desire. We want to identify:

- Timing of spend

- Cash Outflow

- Funding Source

- Lead time of spend

It should look something like this:

We’ve yet to visit the debt side of this equation, which will impact the cash used, so let’s go there now.

CAPITAL STACK STRATEGY & TIMELINES

Once you have your capital needs understood, you need to understand how to fund your capital needs.

There is no one solution for everyone, but here is a brief overview of what the different debt options look like in relation to the capital need:

Typically, you’re matching the duration of the debt to the duration of the asset. Short-term need? Use short-term funding. Long-term need? Use long-term funding.

As you look through your capital needs, understand that lead times to getting the funding secured will typically go up as the length of funding goes up.

- Equipment lease: 14–30 days

- Term-loan: 45–60 days

- SBA 7(a): 60–90 days

- Equity round: 90–180 days

Look at your needs and ensure the timing aligns with the timing needed for the specific deals. Too often I’ve seen people wait to need the funding before seeking it out. In reality, double the timeline and you have the date when you should start shopping for the specific need.

BRINGING THE INDIRECT MODEL TOGETHER

We started with Revenue & Expenses and now have built our Statement of Cash Flows.

We’ve now brought in CapEx and debt. We’ve covered distributions extensively in our SSCF and owner reward posts, so we won’t rehash that here.

Now’s the time to align your capital needs with available funding to keep your cash trajectory on track. Adjust CapEx and debt so that it fits a reasonable scenario and so you don’t run out of cash.

If you want to go deeper and get fancy, absolutely model changes in AR, Inventory, and AP, but that isn’t our first priority here to get something to work with.

At the bottom of the SCF, you should now have a “Change in Cash” for each period, as well as a cumulative cash generation from the business that is close enough to confirm you are generating enough cash to support your capital planning needs.

DOWNSIDE PLANNING

Earlier we talked about three versions of the revenue plan: base, upside, and downside.

Now, I want to spend a bit of time talking about downside. Downside is important because it helps you understand the “yellow” and “red” zones. Yellow being when you should proceed with caution and revisit your plans.

Red being you’ve busted through your downside and need to take emergency action.

Downside planning in your long-term capital plan helps you understand:

- When does your cash fall below your emergency threshold (see our cash reserve calculator here)

- When do debt covenants get tripped?

- What are the first signs of trouble?

All three questions are essential to running a resilient business.

Once you understand these, consider revisiting our past newsletter, where we talked about creating action plans.

Action plans help you “pre-plan” for the bad scenario, so you can make the decision before the “fog” of the moment.

NEXT STEPS

Block 2 hours this week:

- Build a basic revenue & expense 18-month forecast

- Map your CapEx spend, debt, & distributions based on available cash

- Run a downside scenario and see what “goes red” (cash or covenants)

Again: don’t worry about perfect. Just get something started.

Even a rough plan will give you good information as you proceed forward.