Isaac Newton asked why the apple fell straight down.

Einstein imagined riding a beam of light.

Edison questioned every assumption until he held light in a glass bulb.

Feynman picked apart every idea with a childlike intensity most adults lose.

What did they have in common? None of them started with certainty, but instead with curiosity.

And if you want better results from your business, especially your financials, you need to start in the same place.

Yet too often, business culture has no room for “I don’t know.”

The phrase “fake it until you make it” Became popular because everyone was supposed to know the answer. As a founder, CEO, or leader, you’re “supposed” To know the next steps. . Admitting you don’t feels like weakness. So when it comes to understanding our financials, we learn to nod. We hyper-focus on certain patterns but are bad at understanding the full picture.

We’ve been in the business long enough to get a sense of good or bad, but may not ultimately know the why.

You’ve probably done it:

- “Gross margin is down.”

- “Cash looks tighter this month.”

- “Payroll’s creeping up.”

And then what? You accept the trend and move on, filing it under “things to watch.” But you didn’t dig. You didn’t ask the next question. You didn’t test a fix. You didn’t embrace curiosity.

And while financials can be intimidating and hard to understand, I’ll let you in on a little secret: the key to understanding them is asking good questions and being willing to look stupid in the process.

Today, I’m going to give you six ways to ask better questions so your numbers start working for you, not the other way around.

THE FINANCIAL QUESTIONING TOOLKIT

Here are six types of questions to bring into every financial review. Each one is simple, but when used together, they sharpen your thinking, reveal hidden risks, and create space for better decision-making.

ASK: COMPARED TO WHAT?

(Set the baseline)

This is the most underrated financial question in business.

Too many people look at a single number and react. But a number is meaningless until you define its context. Asking “compared to what?” sets the baseline.

Revenue is up… great. Compared to what? Last month? Last year? Your budget? The market Your team’s capacity?

Without a benchmark, it’s just noise.

This question should be built into every financial habit you have:

- Look at gross margin? Ask “compared to what?”

- Review overhead? Ask “is this high or low… based on what trend?”

- See a spike in software spend? Ask “is this abnormal for Q2?”

This is the gateway to all the other questions. If you don’t ask this one first, you’re solving the wrong problem.

ASK: WHY

(Find the root cause)

Once you notice something’s changed, the next step is to dig deep.

The “5 Whys” technique helps you get to the root cause of the issue. Keep asking “why?” until you get past the surface explanation and down to the real system issue or decision-making failure.

Example: Profit margin dropped → Why? → COGS increased → Why? → Freight costs spiked → Why? → We chose a faster vendor → Why? → To hit a last-minute deadline → Why? → We didn’t order inventory early enough.

Now you’re somewhere useful. You’re not just reacting to freight costs, you’re rethinking your planning process.

This works with every line item. Every financial surprise has a chain of cause and effect. Your job is to reverse-engineer it.

And yes, sometimes it’s uncomfortable. You may uncover poor decisions. But that’s what mature businesses do… they learn from their numbers, not hide from them.

ASK: WHAT IF?

(Explore scenarios)

This question is Is like turning on a flashlight in a pitch-black room. It’s lighting your future. By exploring your upside and protecting against your downside, you can go from reactive to proactive.

Ask:

- What if customer churn doubles next quarter?

- What if our biggest customer leaves?

- What if we delay that CapEx spend by 60 days?

- What if we raised prices by 5%, but only on low-margin products?

- What if we offered net-15 terms instead of net-30?

This isn’t about making the best predictions, but thinking through the scenarios. You’re trying to increase your range of preparedness.

The best operators aren’t the most optimistic or the most pessimistic, they’re the most ready. They’ve played out the possibilities. And when one of those “what ifs” becomes a reality, they already have a plan.

ASK: HOW?

(Design solutions)

When you ask “how,” you move from analysis to action. This is where strategy lives.

Russell Westbrook used to play for the Oklahoma City Thunder, which meant that I became a big fan. What I was even bigger a fan of than him was his saying, “Why not?” Too often we assume things are just as they are, and that we can’t change them. But this question of asking, “Why not?” forced you to question your pre-existing assumptions. Instead of focusing on the problems, it gets you thinking about solutions.

Example:

- How can we reduce inventory levels without killing fulfillment speed?

- How do we increase pricing without triggering churn?

- How might we stretch payroll another two weeks without cutting staff?

This question forces you to zoom in on levers you control and see what can be adjusted. It also surfaces constraints andthings that may be harder to change than you think.

By thinking outside the box, you can gain an advantage over your competitors. Some of the biggest business innovations in history came from owners who looked at other industries and asked, “How can I apply that in this business?”

ASK: WHAT’S MISSING?

(Spot blind spots)

Here’s a truth most financial reviews avoid: sometimes the problem isn’t in the data, it’s in the absence of data.

Ask:

- Are we tracking profitability by product line?

- Do we know our CAC by marketing channel?

- Do we have a budget for this team at all?

Or, even simpler:

- We cut spending, but did it affect results?

These are the questions that expose structural gaps in your reporting, your process, or your thinking.

Sometimes the data is fine, but the story is incomplete. By asking “what’s missing,” it helps you spot your blind spots. It makes sure you’re seeing the whole picture, not just the pieces someone handed you.

ZOOMING IN & ZOOMING OUT

(Adjust perspective)

In business, it’s really easy to get into the Groundhog Day mentality: every day is the same.

So sometimes we have to force perspective shifts. This tool is all about balancing that same as usual mentality and forcing yourself to get outside of it.

First, we zoom in: Go deep on a single line item or customer or KPI. Look at its trend, its drivers, its history. Ask: do I really understand what’s happening here?

Then, we zoom out: Step back and ask: is this part of a broader pattern? Does this issue show up across departments, customer types, or regions? Is it seasonal? Market-driven?

Most bad financial decisions come from doing just one or the other. Either you’re too zoomed in fighting tactical fires, or too zoomed out floating in abstraction.

Strong financial leadership toggles between both, on purpose.

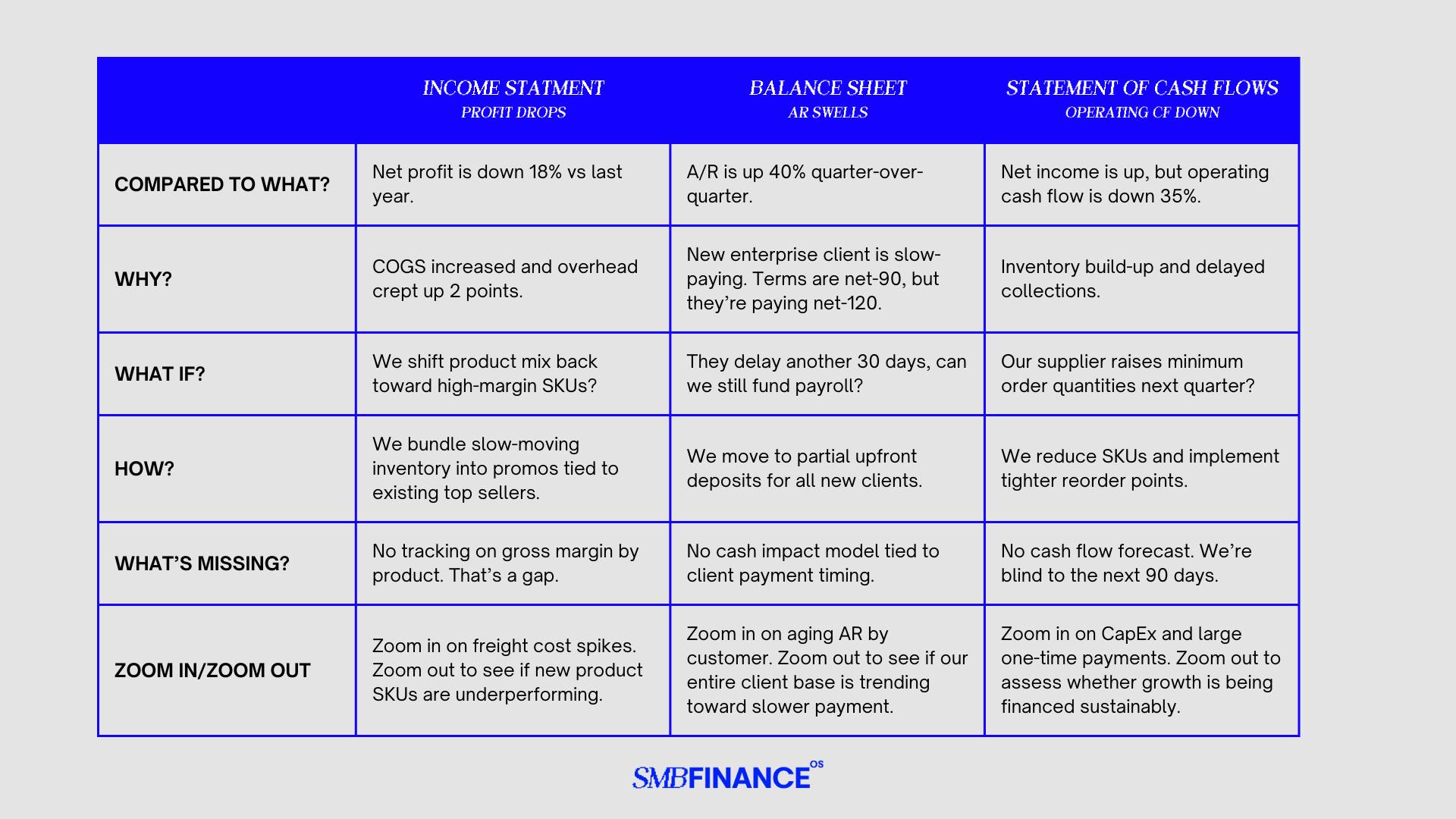

APPLYING THE TOOLS TO YOUR FINANCIALS

Here are some examples of what it looks like to apply these questions in practice:

INCOME STATEMENT: PROFIT DROPS

- Compared to what? Net profit is down 18% vs last year.

- Why? COGS increased and overhead crept up 2 points.

- What if? We shift product mix back toward high-margin SKUs?

- How? We bundle slow-moving inventory into promos tied to existing top sellers.

- What’s missing? No tracking on gross margin by product. That’s a gap.

- Zoom in/out: Zoom in on freight cost spikes. Zoom out to see if new product SKUs are underperforming.

BALANCE SHEET: AR SWELLS

- Compared to what? A/R is up 40% quarter-over-quarter.

- Why? New enterprise client is slow-paying. Terms are net-90, but they’re paying net-120.

- What if they delay another 30 days, can we still fund payroll?

- How? We move to partial upfront deposits for all new clients.

- What’s missing? No cash impact model tied to client payment timing.

- Zoom in/out: Zoom in on aging AR by customer. Zoom out to see if our entire client base is trending toward slower payment.

STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS: OPERATING CASH FLOW DOWN

- Compared to what? Net income is up, but operating cash flow is down 35%.

- Why? Inventory build-up and delayed collections.

- What if our supplier raises minimum order quantities next quarter?

- How? We reduce SKUs and implement tighter reorder points.

- What’s missing? No cash flow forecast. We’re blind to the next 90 days.

- Zoom in/out: Zoom in on CapEx and large one-time payments. Zoom out to assess whether growth is being financed sustainably.

BUILDING A CULTURE THAT REWARDS CURIOSITY

If you want these questions to live beyond a single meeting, you need to create a culture where curiosity is respected… where it’s safe to ask, explore, and test.

For me, this meant requiring people to come to me with problems, but only after they had some attempts at solving it. When employees would come to me, I’d say, “Great, what did you try?” If the answer was nothing, I’d send them back to troubleshoot some things on their own.

It’s about encouraging that curiosity and problem-solving instead of just wins.

I broke this down into a few rules:

- Don’t bring naked problems. If you show up with a problem and no attempt to solve it, that’s a miss. But if you bring the problem and show what you tried, even if it didn’t work, you get celebrated. That’s learning in action.

- Celebrate questions. If someone on your team says, “I noticed this number changed, why?” that’s a win. Don’t gloss over it. That’s the kind of thinking that catches million-dollar mistakes early.

- Make experiments small and fast. The best fixes come from lightweight tests. Try something for 7 days, track the result, adjust. Don’t wait until it’s “ready.”

- Close the loop. A question led to a test, which led to a result, which led to a decision. That loop builds momentum and eventually a system.

FINAL CHALLENGE

At your next financial review, don’t just read the numbers. Engage them.

Pick one line item or ratio that looks off. Then run it through the toolkit:

- Compared to what?

- Why?

- What if?

- Ho

Don’t stop until you’ve tested at least one fix.

The best financial insights don’t come from the numbers themselves. They come from the questions you’re willing to ask about them.